I’ve mentioned before that pride comes before a fall. Today proved this once again: this was a frustrating and disappointing lesson.

The Pride

Driving up to the airfield today I was in a buoyant mood. The music on the radio was energetic and positive, and I knew today would either be another revision lesson or circuits.

Another revision lesson would be easy as I was confident in my flying abilities and circuits would be great fun and a good chance to correct a mistake I’ve been dwelling on from the previous lesson; specifically, how quickly the little Cessna lost altiude when pulling the power in short final, just before landing, requiring the instructor to intervene.

On arrival my instructor and I went into the briefing room. “We’ll do another revision lesson today,” he said before turning on the TV attached to his laptop.

Oh no.

My nemesis.

“We’ll do stalls 1, clean, base to final and approach.”

I hate stalls. They feel so unnatural and out uncontrolled. As a control freak, immediately I started to worry.

You don’t know a plane until you’ve stalled her

– Me, just now

Having only had one lesson in sexagenarian Cessna 150, G-ASZU, I was still getting to grips with her unique quirks and ‘feel’. The uncertainty of knowing how she would stall was playing on my mind. I’ll put any pilot bravado to one side for a moment and be completely honest: the idea of stalls scare me.

Pre-Takeoff Checklist

The lesson started with a bit of cludging around by me: I couldn’t find G-ASZU’s fuel drain point and the plane’s fuel check bottle was missing, so by the time the instructor joined me at the aircraft I was barely half way through the checklists than I should have been. He had to borrow a bottle from another aircraft and then had to show me where the drain point was (just behind the doors at the lowest point of the wing/fuel-tank structure, which makes total sense).

Sheepishly, I got in and started going through the rest of the checklist when I spotted something on the horizon.

It was a helicopter but it looked very sleek. Not your usual Robinson trainer chopper.

My instructor jumped in and said we needed to get going. The 3 training aircraft of the flight school’s fleet were departing together and we needed to go.

I started the engine and ran the ROSAMS checks, then while I spent a whole 5 minutes trying to find and get my seatbelt fastened (aware we’d shortly be semi-controlled falling out of the skies over Northumberland) the instructor took control and taxiied us along to the holding point.

We ran our checks quickly and overtook G-AWUJ – the other flight school Cessna and my previous training steed – by backtracking the runway and I did the take off, running through the ATP checks in chorus with my instructor.

Once airborne, I missed the altitude to raise the flaps and had to be prompted, failed to compensate enough for the cross wind and drifted left off centreline and then got distracted when another Cessna appeared in our windscreen above us.

“Traffic, 12 o’clock high,” I said.

My instructor confirmed and said, “very good, well spotted.”

So at least some of my airmanship remained in my head.

We turned left, performing a crosswind departure to the east – this is not normally the preferred way to leave the circuit as the ‘dead side’ for that runway is to the left and you could conceivably run into a NORDO (no-radio) aircraft descending deadside.

For us, with a right-hand circuit, the dead side was on our left.

On this occasion, we had great visibility and were sure there was nothing out there. I climbed up to 3,000ft in a Vy climb and headed out over the coast. It’s not really spoken about explicitly, but you do stalls training over empty areas, just in case something happens and you can’t recover the aircraft. We do a “not flying over a built up area” check, but that’s it.

Clean as a Whistle

After a clearing turn, I did a clean stall, which I was fairly confident I could handle.

I pulled out the carb heat and reduced power to idle, holding the nose up to maintain 3,000ft at the expense of our airspeed which started to drop precipitously.

One thing to note on this particular aircraft – it didn’t have a working stall horn, which is a loud audible squeaker that sounds when the wing is about 5-10 knots of air flow away from stalling, so my instructor was playing a dual role as instructor and stall horn.

For clean stalls, we can go into an ‘established stall’ pretty safely, in fact if you just let go of the controls whilst in an established clean stall the Cessna will – by design – recover itself.

OK, for pedantic pilot types, there would be some situations where the Cessna wouldn’t do this such as out-of-trim and out of balance conditions etc but it’s as close to being absolutely true to make no difference.

I held the nose up trying to keep 3,000ft on the altimeter while the airspeed dropped below Vs (clean stall speed), denoted by the bottom of the green arc on the air speed indicator (ASI). The aircraft started to show its discomfort by becoming unstable, the wings wobbled and the nose tried to drop. It was impossible (at least to me) to tell but the altimeter showed we had started to descend rapidly, over 1,500ft/minute.

“Squeeeaaaaaak!” said my instructor / stand-in stall warning horn. “And recover. Full power.”

I released the back-pressure on the controls and the nose immediately dropped, allowing us to regain vital airspeed. I pushed the throttle to max power and very quickly we sped up. I tried and failed to catch the aircraft at 60 knots of airspeed to start a Vy climb and regain our lost altitude.

“Full power?” prompted the instructor.

I’d left the carb heat on, which saps power from the engine and doesn’t help in a situation where you need power like stall recovery.

Pushing in the carb heat, the engine gave us another 100rpms and another 50ft/minute of climb rate – which could make all the difference if you find yourself in that situation in high terrain.

And I climbed us back to 3,000ft. Another HELL check and I did another clean stall, waited for my instructor to squeak, and recovered this time only losing a couple of hundred feet while the first cost us 600ft of altitude.

“No problems with that, let’s try a base to final stall.”

The Pilot Killer

This is where the wheels started to fall off. Not literally thankfully, working undercarriage is very important.

This stall simulates a common killer of newbie pilots – the base-to-final stall.

The situation is you’re turning to line up with the runway fully configured for landing – 20 degrees of flaps, 1500rpm engine power, low to the ground so little room for stall recovery, but you overshoot the centre-line of the runway and pull back the controls to turn sharper. This increases your angle of attack and, given your low power configuration, your speed bleeds away, putting you in a dangerous, low-energy situation and an impending stall.

We’d be doing this at 3,000ft to practice, plenty of altitude to mess up!

And mess up I did.

If a stall occurs when turning you need to reduce the angle of attack first – BEFORE levelling the wings. Levelling the wings requires use of the ailerons at the tips of the wings and operating these can further increase the angle of attack of the wing, causing a deeper stall. You don’t wait for the stall to become fully established, you take immediate action as soon as the stall warning horn activates. I won’t dwell on the technique because I’ve covered it before but recovery is straight forward:

- Control column centrally forward while applying full power

- Close the carb heat if activated (usually is on approach)

- Level wings once stall is mitigated

- Climb back to original altitude / height

- Raise flaps in stages once climbing safely

For some reason I just couldn’t get it to work – my hands would start operating the ailerons before fully mitigating the stall situation, I’d continue to push the throttle forward but leave the carb heat sapping energy from the engine (not great with 20 degrees of draggy flaps hanging off the wings) and I’d not climb soon enough which meant we came close to exceeding the speed at which the flaps should be out. It was a cluster, and the more we tried the more frustrated I got and the more mistakes I made. That my instructor was squeaking comically in my headset didn’t make things any easier.

He could sense I was beating myself up and took the controls for a moment. “Let’s leave it there. Have you tried a spin before?”

The Fall

I’ve seen spins, they look awful. My previous instructor said we couldn’t do them because the previous training aircraft wasn’t certified for aerobatic flight, so I was dubious that trying it in an older model was a sensible thing….

“No…” I said. Trying desperately to trust the instruction, as I’d learned before.

A spin is a “yaw aggravated stall”, which means that the aircraft is stalled but a yaw (left or right pivoting motion) moment is applied to cause the aircraft to tumble about its vertical axis. You lose a lot of altitude quickly in a spin.

The instructor took us out over the North Sea and pitched the nose up. I watched the needle of the air speed indicator (ASI) drop. I felt the aircraft wobble again as we entered the stall and I expected the instructor to boot the rudder pedal to start the spin but before he did that he pulled back sharply on the controls making sure the stall was fully established. Then, like a 3 dimensional handbrake turn, the tail of the aircraft swung from pointing at the ground to pointing at the sky, and the left wing went from pointing at the horizon to my left to pointing at the sea, then the sky, then the sea again. It was like being in a washing machine. The windscreen was filled with just sea, spinning around anticlockwise.

PLEASE NOTE – the following video is VERY loud so please turn your volume before pressing play…

After two complete spins, the instructor calmly said, “push forward, reduce power, full opposite rudder.”

The spin stopped, our wings levelled and the instructor began to gently pull us out of the nose-dive. The adrenaline rush was intense and I involuntarily whooped into the intercom making the instructor laugh. “Did you enjoy that?” he smiled.

Overhead Join and Landing

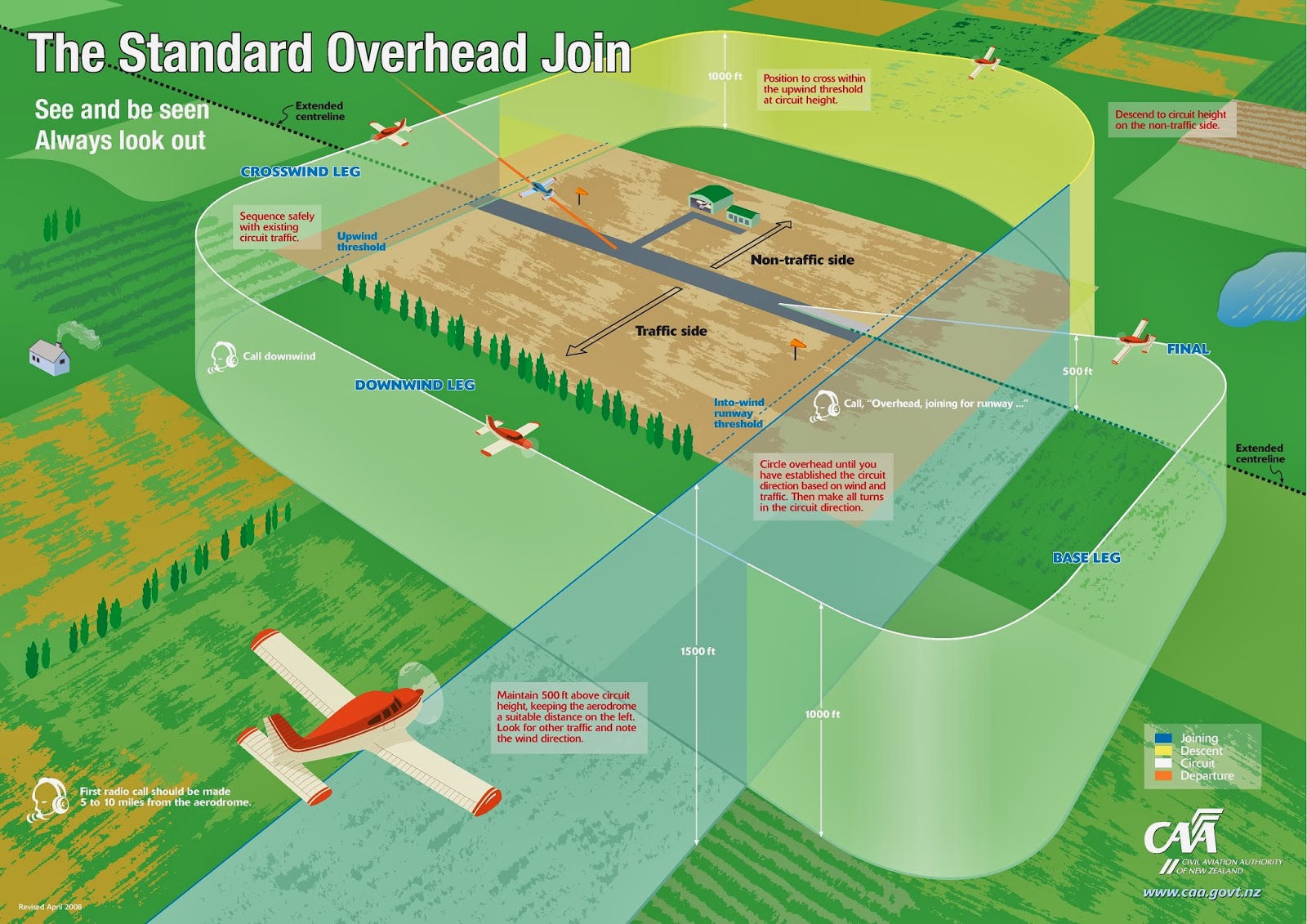

The instructor handed back the controls to me and I flew us back towards the airfield, making a good radio call notifying traffic at the field that we were “inbound for standard join runway 19”.

I confirmed using the windsock that 19 was the most appropriate runway and descended deadside to 1,000ft aal, pattern height before turning crosswind and then onto downwind.

I ran a quick BUMFILCH and then radioed, “Golf-Zulu-Uniform, downwind runway 19.”

I turned onto base (feeling a little strange after so much intentional stalling) and then carefully onto final, about 100ft high but still comfortably within the flight envelope. I modulated the power to bring us down onto the glidepath and as we got near the threshold I cut the power, taking care to raise the nose more than the last time.

I gently danced on the rudder pedals to keep us straight and on the centreline and progressively pulled back on the controls to arrest our descent rate. We touched down quite nicely, I proceeded to slow the little Cessna down and park her where I’d found her earlier that morning. Although I was pretty happy with the landing my instructor said I’d landed all 3 wheels at the same time which is discouraged as the front wheel isn’t designed to be as strong as the two main landing gear, but it wasn’t too bad. “At least it wasn’t nosewheel first,” chuckled my instructor.

Debrief

The actual debrief wasn’t particularly noteworthy, I knew what I’d messed up.

But on the drive home I played through the actions in my mind:

- Controls forward, full power

- Carb heat in ASAP

- Level wings while climbing out to prevent overspeeding the flaps

- Flaps up in stages

And when I got home I spent a couple of hours on X-Plane 12 stalling, clean and base-to-final as well as final approach stalls which we’ll be doing next time. Flight sims will never replace actual practice but for building muscle memory I find it very helpful. Your mileage may vary.

While I trusted my instructor wouldn’t do anything unsafe I was curious why we were able to do spins in an older, non-aerobatic 150 and it turns out there’s a known issue with the newer models with the swept-back tail fin during spins whereby the rudder can become stuck at full deflection. These should be fixed by the addition of rudder stops but it makes sense to just not do spins in these newer models, whereas the beautiful straight-tail of the 150E we flew today can spin all day long.